I have no choice but to be honest. A mere year ago, I had no idea what a makerspace was, what makerspace-thinking entailed. Nor had I any inclination as to how successful either of those two things would be in a library setting. During the beginning of PCL’s partnership with FabNewport, PVD Young Makers, I worked as a Youth Services Specialist at Mt. Pleasant library, a branch with heavy traffic, and an ongoing demand for young adult and teen programming. Resulting from the hard work of Francesca and others, I witnessed a space—which I thought of as certainly handling the occasional craft—become a space of daily, incessant creativity. I witnessed intricately designed cardboard Thanos gloves, t-shirt graphics honoring local sports teams and dead loved ones, hand and machine-sewn stuffed animals, all of them indisputably meaningful objects. I had no idea how a program like this would sustain itself, yet it did. It really did. A maker-culture sprung up from the youth patrons, rather than being imposed on them from above, just as I always hoped it would.

When it came time for me to fulfill my role as Programs Director of the Mobile Library, and when it came time for me to begin planning activities, it more than delighted me to hear that FabNewport would be by my side for many of those days of outdoor, on-the-fly programming. Three days a week for the entire 8-week program, in fact, FN sent members of their dedicated team to the mobile library.

Though I had seen the maker-ethos work wonders in the creative capacities of youth in the library buildings, I still hesitated to grant any kind of predetermined success translating it to the mobile setting. For one, it was outside. This meant that we would not have central storage, other than the library bus, itself, and the delicate space of our own vehicles. And so this meant that we would need to improvise both the creation of the “space,” which looked different at every site, and the implements with which the youth would be encouraged to “make.” This led to the next difficulty. During our first afternoon with FN, we saw over 100 youth, ages 3-15. While it bade well for outreach, it bade very, very terrifying for the number of supplies we had anticipated using. I say “terrifying,” but this is the sort of thing any Youth Services Specialist thrives on: determining a problem and, acknowledging the how little time and money one has at one’s disposal, finding a solution. We never really had a solution; rather, solutions that morphed over time, yet remained faithful to the interests and attentions of the youth we served.

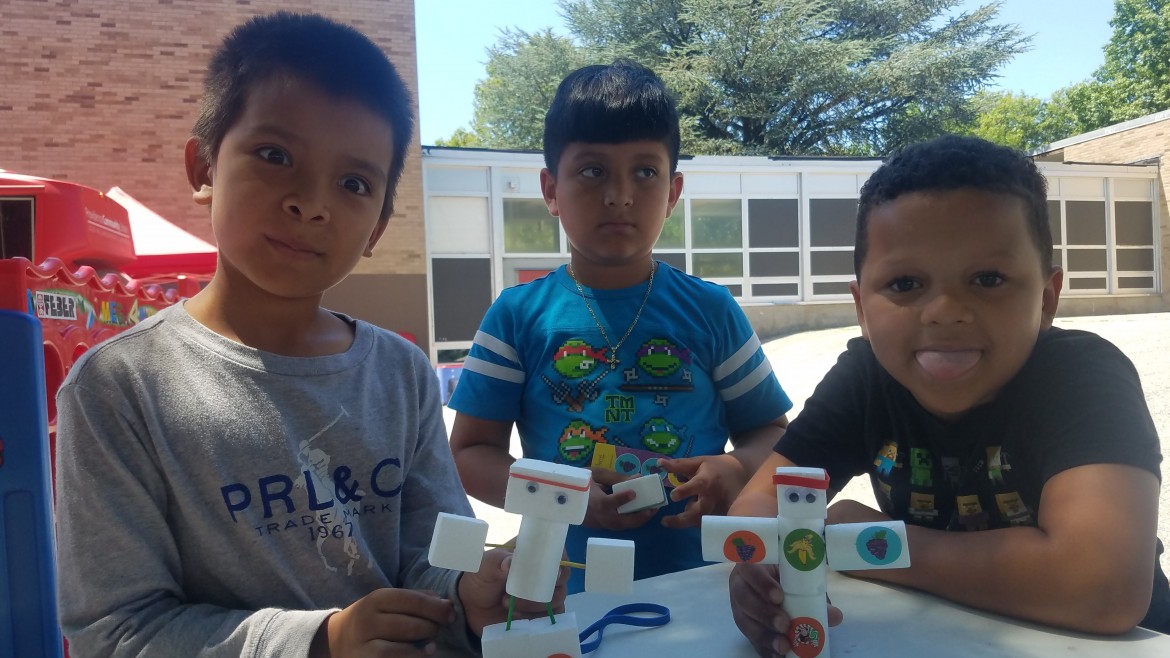

We realized after that very busy first afternoon that the usual everything-goes disposition we applied to programs within the libraries needed to be refined. We certainly didn’t want to deprive the makerspace of its characteristic freedom, though. Sometimes we offered open-ended prompts, such as the day at William D’Abate when FN’s Seiji brought a bunch of electric toothbrushes, batteries, and a wide array of craft materials and simply suggested the kids “make something electric that can cool you down.” Not everyone stayed to script, of course. In a makerspace setting, it’s the deviations that count. I think I saw only one fan-looking object, but in addition, I saw helicopters, pen-robots, color-wheels. These young makers bounced ideas off each other, offered assistance, and followed their own wild associations in directions we never could have imagined.

Similar work happened when we offered prompts with constraints, such as when Josie and I gathered the scraps of previous weeks’ activities and challenged our visitors to make the tallest towers without adhesive. As it were, we had recently run out of those supplies ourselves—glue, tape—and needed to act fast. What resulted was makerspace majesty. I don’t think I’ve ever seen so many attempts, near-failures, and on-the-spot re-imaginings in one two-hour period. The question that we posed—How to make a structure under specific conditions—led them to question the very general basis of structure itself. Gravity was not on our side, and lucky for engineering, it never has been. Everyone came away from the experience enriched with possibilities. And, if I’m still being honest, I think some artists were born.

This sentiment wasn’t restricted to a specific session. I sensed the whiff of art-making anytime hands touched material. Whether or not any of these young individuals we visited will become artists in the professional sense of the word, I truly feel we facilitated the inception of artistic thinking. We used mostly recycled products, encouraged the youth to repurpose their own materials, and asked vital questions regarding the sanctity of resources. Introducing this maker-philosophy to our public programming has fostered a new generation of creative, ethical intellects in Providence, RI. I don’t mean to say that we gave them a trade. I’ve never been a proponent of any sort of programming that would impose a predetermined form onto the youth’s productions. What I believe we offered them was something they are rarely permitted at home, in school, and certainly won’t be permitted in their future workplaces (at least, not as much as they deserve)—we gave them permission.